Two Explorers from Bennington

Daniel Harmon and Simon Fraser, both from Bennington, were explorers of the early nineteenth century. Both men were born during the American Revolution. Each of them left Bennington and moved to Montreal. They both joined the same fur trading company and both represented that company in western Canada during the first 20 years of the nineteenth century. They explored the western regions of North America before Lewis and Clark made their much more famous trip. And they stayed longer, nearly 20 years. Unlike Lewis and Clark, however, Fraser and Harmon have all but been forgotten by history.

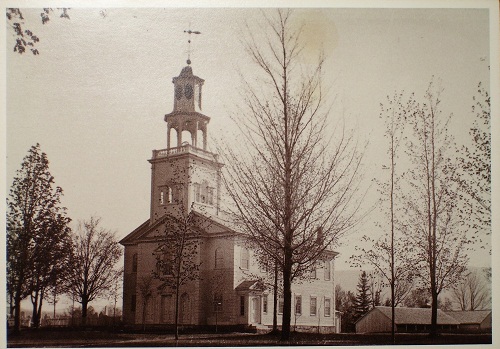

Daniel Williams Harmon was born on February, 19, 1778, about 1 mile northeast of downtown Bennington. His father, David, had married Lucretia Dewey in July 1770. Lucretia was the niece of Jedediah Dewey, the first minister of Old First Church located in what is now known as Old Bennington. Lucretia was the daughter of Martin Dewey and was from Westfield, Massachusetts, which is where Jedediah was recruited from. The congregation built Jedediah a house as part of the enticement to bring him to Bennington in 1763. That house still stands. It is on the southeast corner of what is now known as the Old Green in Old Bennington. Jedediah’s son Elijah built a tavern next to the first meeting house, which was located on the west side of the Old Green, directly across from the Old First Church. Dewey’s Tavern later became known as the Walloomsac Inn and still stands today. Elijah was a Captain of a local militia unit during the Battle of Bennington. David Harmon built and operated Harmon’s Tavern, which was on the corner of what is now Vail Road and Airport Road about 1770. On August 14, 1777, General Stark had breakfast at Harmon’s Tavern on his way to the Battle of Bennington. As a Patriot and a sergeant in Captain Dewey’s militia company, David Harmon fought in that battle as well.

On February 19, 1778 Daniel was born at Harmon’s Tavern. At the time, road was fairly heavily traveled, with people going to and from Canada. This would explain why the family headed north after the War.

In the summer of 1796, the Captain moved his family to Vergennes, Vermont. Daniel was 18 years old. In 1798, at age 20, Daniel moved to Montreal, where he worked with McTavish, Frobisher and Company. In April 1800, he transferred to North West Company. It was the North West Company that sent him to western Canada. He traveled by large canoes that were manned by 8-9 people and carried up to 3 tons of supplies. 10 canoes equaled a brigade and 3 brigades made up a squadron. This was a big operation and was undertaken years before President Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark out to explore the northwestern portion of what is now the United States.

In October of 1805, Daniel took Elizabeth as a partner. Born of a Canadian Father and Snare Indian mother, she was 14 years old (half as old as Daniel) at the time. Together they had 14 children, 10 of which survived childbirth. They were married in 1819 at Fort William on Lake Superior.

Daniel lived 20 years in the West, 8 ½ years west of the Rockies. In 1820, he published Journal of Voyages and Travels . This is an impressive accounting of the Indians living west of the Rocky Mountains as well as the fauna and flora of the region. As long as he lived out there and as much as he had explored, Daniel never actually reached the Pacific—it simply was not important to him.

The North West Company merged with the Hudson Company in 1820 and Daniel resigned from the Company in 1821. He returned to Vergennes, Vermont in the fall of 1820, and then moved to Coventry where he helped develop the town. Coventry had had a population of 7 (James Moore family) in 1800 By 1820, it had 50 families and at one point it was renamed Harmonsville. Daniel moved his mother and brother Calvin to Coventry in 1822. His mother died 1829. His father had died in 1805.

Daniel moved in 1840 or 1841 to Sault-au-Rocollet and died April 23, 1843 in poverty.

Simon Fraser was two years older than Daniel Harmon. He was on born May 20, 1776, about 3 miles west of present day Bennington, Vermont in the small rural hamlet of what was then called Mapletown or Mapleton, in what is now Hoosick Township, New York. His father’s farm actually sprawled across what is now the state line, being part in current day Vermont and part in current day New York. The approximate location of the home is marked on the east side of the road running north off NY Route 7, just west of a building. Mapleton probably cannot be found on any modern map.

Simon’s father, also Simon Fraser, and his mother, the former Isabella Grant, emigrated from Scotland in 1773. They bought land within the boundaries of the “New Hampshire Grants”, chartered by Governor Benning Wentworth in 1749, which originally defined the boundaries of Bennington, 17 or 18 years before the boundary line between New York and Vermont was finally established, going through the middle of what was the farm upon which Simon was born. His cousin Hugh had settled in that area in 1764, when he bought 500 acres within the township of Bennington.

Simon senior was a Loyalist, whose sympathies led him to join General Burgoyne’s forces at the Battle of Bennington. He escaped from that battle over a bridge to Cambridge. He was later arrested in 1777 and a portion of his farmstead was confiscated by the authorities in Bennington. He died in prison in 1779.

Even after the peace of 1783, Fraser’s family was harassed by their American neighbors. Consequently in 1784, Isabel Fraser sold the farm in Mapleton, and, like thousands of other Loyalists, fled to Canada with her young family. Simon was only eight years old. At first the family lived with Isabel’s eldest son, William, at Coteau du Lac. Later, she moved the family to St. Andrews West, near Cornwall, Upper Canada, where her second son, Angus, was already farming the family property. About 1790, Simon was sent to stay with his uncle, John Fraser, a prominent judge of Common Pleas Court in Montreal. Under his uncle’s care, Simon attended school for two years before joining two of his cousins, Peter and Donald Grant, in the fur trade.

In 1792 he became an apprentice clerk in the North West Company of Montreal and was sent to learn his trade in Athabasca in 1793. He became a partner in 1801. In 1802, he was sent to the North West Territory as a superintendent of the North West Company. As a partner, Fraser was selected to oversee the extension of the company’s activities to the land west of the Rocky Mountains from 1805-1808. His mandate from the North West Company was to cross the Rockies and establish trading relations with the Indians in the interior of what is now British Columbia, but which Fraser called New Caledonia. Here he established Fort McLeod in 1805, Fort St. James and Fort Fraser in 1806, and Fort George in 1807.

Establishing a trade route to the Pacific had become a priority for the North West Company. Its officials gave Fraser the task of exploring a river believed to be the Columbia to its ocean outlet. This river, which he so successfully navigated, turned out not to be the Columbia, but rather an unknown river which fellow Nor’wester David Thompson would later name the Fraser River. It is to this voyage that Simon Fraser owes his fame. On May 28, 1808, Fraser and a company of 23 men set out from Fort George to follow the river to the Pacific. Their harrowing journey, 520 miles in length and 36 days long, revealed both the ruggedness of the British Columbia interior and the courage of those who traversed it. Their expedition culminated in Fraser’s discovery of the mouth of the river at Musqueam. Following his exploration of the “Fraser” river, Simon Fraser returned to the Athabaska department of the North West Company. In 1816, although endeavouring to retire from his life in the fur trade, Fraser found himself embroiled in a conflict between the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company over Lord Selkirk’s Red River settlement, which ended in the Seven Oaks Massacre. As a partner in the North West Company, Fraser was one of several men charged in the affair. However, when the case was tried in 1818, he and the others were acquitted of all charges. The trial coincided with the end of Fraser’s career in the North West Company.

In 1818, he moved to St. Andrews West where his brother, Angus, and his sisters already resided. Eventually acquiring 500 acres in Cornwall Township, Simon Fraser built a sawmill and a gristmill. Unfortunately, both mills proved unprofitable.

His final years in St. Andrews West were, however, not entirely without reward. On June 7, 1820, Simon Fraser married Catherine MacDonell (of the Scottish Leek family) with whom he had nine children including a daughter who died in infancy. In 1838 Fraser, at the advanced age of 62, took up arms in defense of Canada during the Rebellion. In the dark he fell down a flight of steps and seriously injured his right knee. Now permanently disabled, he was forced to apply to the government for a small pension, which he eventually received in 1841.

Simon Fraser died aged 86 on August 18, 1862. Happily united in life for over 42 years, the couple was not long separated by death. His wife died the next day. Simon and Catherine Fraser were buried in a single grave, which exists to this day in the Roman Catholic cemetery at St. Andrews West.

Although Simon Fraser and Daniel Harmon, were both born in Bennington and lived, for their first few years, within three or four miles of each other, and although they both lived in Montreal and both worked for the North West Company, it is not known whether or not they ever knew each other. What is known, however, is that each of them made significant contributions to the exploration of North America well before and for a longer period of time than subsequent explorers, who would be given a much greater representation in its history.