Enslaved at the Catamount Tavern

Callie Raspuzzi, Collections Manager, Bennington Museum

A Black woman named Margaret Bowen (called Peg) was enslaved by Captain Stephen Fay in Bennington from 1772-1778. At the time, Fay was the proprietor of the Catamount Tavern on what is today Monument Avenue. Slavery was not uncommon in the northern colonies, and there are several examples of early white settlers bringing enslaved Black people with them to Bennington. The Black population in 18th-century Vermont is hard to calculate. When the first Federal census was taken in 1791 after Vermont joined the Union, there were 20 Black people counted in Bennington out of 2,350 total.

Peg was born around 1742. She was acquired by Moses Porter of Hadley, Massachusetts, in 1754 after he constructed a grand new house on a property he named “Forty Acres.” When Porter died in 1756, his estate inventory listed two enslaved people, Peg and Zebulon Prutt, who were inherited by Porter’s daughter and son-in-law Elizabeth and Charles Phelps, Jr. Peg had two daughters, Rose, born July 2, 1761, and Phillis, born June 2, 1765.

In May 1771 Peg and another enslaved man named Pompe Morgan requested that the town clerk in Hadley record their intent to marry. They needed the consent of both of their enslavers, which Pompe’s enslaver Jonathan Warner refused to give. Peg seems to have had more agency. In August of 1771 she “went out for herself,” an arrangement in which she worked for another family, but her enslavers collected her wages. She may have been allowed to keep a portion of the money, or she might have sought this arrangement simply to be nearer her intended spouse. Nearly a year later a solution presented itself. Stephen Fay, in Bennington, would purchase both Peg and Pompe together; presumably Pompe’s enslaver had given in. At this point, it appears Peg was given a choice. She could go to Vermont with her lover, or stay in Massachusetts with her children (Rose and Phillis were 11 and 7 years old). She chose her husband.

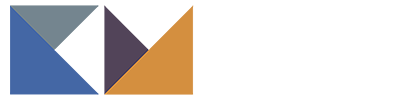

We know very little about Peg’s life in Bennington. Back in Hadley her daughter Rose gave birth April 18, 1775. Three days later Peg’s other daughter, Phillis, died of tuberculosis and the new baby was named after her. Peg did not meet her granddaughter until she was sold back to Charles Phelps, Jr. on March 6, 1778, for twenty pounds. We do not know what happened to Peg’s husband Pompe. He may have died in Bennington, been sold to another enslaver, or perhaps gained his freedom.

There was a great deal of ambivalence regarding slavery in early Vermont. The Vermont Constitution, signed July 8, 1777, declared an end to adult slavery, but in vague language and without any provision for enforcement. The first article of Chapter I stated “That all men are born equally free and independent…Therefore, no male person, born in this country, or brought from over sea, ought to be holden by law, to serve any person, as a servant, slave or apprentice, after he arrives to the age of twenty-one Years, nor female, in like manner, after she arrives to the age of eighteen years, unless they are bound by their own consent, after they arrive to such age, or bound by law, for the payment of debts, damages, fines, costs, or the like.” The Constitution’s use of weak wording (“ought” instead of “shall”) might have been intentional.

Stephen Fay’s son Jonas was the witness of Fay’s 1778 sale of Peg. Jonas Fay was a delegate to the 1777 constitutional convention in Windsor and is generally credited as the Constitution’s primary author. Just because the Constitution was signed did not mean that everyone abided by it. There was no ratification process, many people opposed the new government, and a difficulty in printing even delayed the first elections. People like the Fays clearly did not think the prohibition of adult slavery was binding. On October 24, 1778, the Vermont legislature appointed a committee to prepare a bill regarding the freedom of slaves, but no bill was ever presented, and no record exists of their actions.

Both Stephen and Jonas Fay were aware of the fact that enslaving people was against the spirit of the new Constitution, if not the letter of the law. Presumably Peg herself was either not aware or was not in a position to do anything about it. Peg’s value at twenty pounds was far less than her appraised value of 33 pounds and change in 1756, and it is possible that Fay chose to sell her at a loss rather than acknowledge the freedom that was rightfully hers. It is also possible that her value to her enslavers had fallen due to her age and the end of her prime childbearing years.

There are other examples of respected Benningtonians enslaving people after 1777, including David Avery, the second pastor of the Old First Church, and Moses Sage, North Bennington’s most prosperous citizen. Fay did have contemporaries who were very much opposed to slavery and actually acted on their beliefs. After Ebenezer Allen captured a Black woman and her young daughter, who had been enslaved in Burgoyne’s army, he freed them. He did not cite the Vermont Constitution in him manumission notice, recorded in Bennington by the Town Clerk on November 27, 1777 but stated, “it is not right in the sight of God to keep slaves.” Other Vermonters may have felt the same way, but most, like Jonas Fay, were silent witnesses.

A year after Peg returned to Hadley, her daughter Rose became sick. She continued to battle what appears to have been tuberculosis until her death March 14, 1781. She was only 20 years old. Her daughter Phillis (Peg’s granddaughter) also suffered from tuberculosis and died two years later.

Peg finally gained her freedom in May 1782. Whether the Phelps family had formally manumitted her or she purchased her freedom is, again, unclear. There were several court cases taking place in Massachusetts at this time which ended up making slavery untenable in the state.

When Vermont joined the United States in 1791, it was (on paper) a free state. The first Vermont state census reported only free Black people in the state. The Vermont Gazette, printed at Bennington by Anthony Haswell, in its issue of Sept. 26, 1791, stated, “The return of the marshal’s assistant for the county of Bennington shows that there are in the county…17 black males over 4 and under 16; 15 black females. Total of inhabitants 12,254. To the honor of humanity, no slaves.”

The Gazette’s assertion was naive and optimistic. There were indeed examples of enslaved Vermonters up through the 1840s at least, and to our shame, slavery’s legacy of racism still haunts us.

The story of Peg and Pompe appears in the books Earthbound and Heavenbent by Elizabeth Pendergast Carlisle and Entangled Lives by Marla Miller. We would like to thank Ruth Ekstrom for bringing Peg’s story to our attention. We owe a great debt of thanks to Carolynn Duffy for her help in researching the lives of Peg and Pompe. Research is ongoing. If you would like to be involved, please contact Callie Raspuzzi at craspuzzi@benningtonmuseum.org.

Receipt from Stephen Fay to Charles Phelps for Peg, March 6, 1778

Receipt from Stephen Fay to Charles Phelps for Peg, March 6, 1778

Porter-Phelps-Huntington Family Papers, Robert S. Cox Special Collections and University Archives Research Center, UMass Amherst Libraries.

Stephen Fay sold Peg back to Charles Phelps after the 1777 Vermont Constitution forbade slavery in the new republic. This receipt is witnessed by his son Jonas Fay, who is credited with writing the Constitution.

1992.103.13

Catamount Tavern Postcard, ca. 1920-1925

Catamount Tavern Postcard, ca. 1920-1925

Published by ET Griswold, from a drawing by J. Lawrence Griswold

Bennington Museum Collection, Gift of Jane A. Haviland

The Catamount Tavern, where Peg was enslaved, was located on the corner of what is now Monument Avenue and Main Street in Bennington. It was built by her enslaver Stephen Fay around 1768- 1770. The building was famous as the meeting place of the Green Mountain Boys during the controversy between the New Hampshire grantees and New York and during the Revolutionary War. The building burned down March 30, 1871.