For Immediate Release: July 24, 2019

Contact: Susan Strano, Marketing Director

802-447-1571 ext. 204

[email protected]

Images:

Romaine Tenney and a Highway Official Survey the Tenney Farm, Ascutney, Vermont, 1964

Donald Wiedenmayer (1917-2013)

Inkjet print from scan of original negative, 10 x 12 ¾ inches

Courtesy of the Vermont State Archives and Records Administration

Young Man Holding a Peace Candle at Vietnam Moratorium Rally, Bennington, 1969

Greg Guma (b. 1947)

Inkjet print from scan of original negative, 13 ¾ x 9 inches

Courtesy of the artist

Sow the Seeds of the Revolution, 1970

Published by Free Vermont, Artist/Designer Unknown

Ink offset printed on newspaper, 22 x 17 inches

Collection of the Vermont Historical Society

Phillip [sic.] H. Hoff Campaign Poster, 1962

Designer unknown

Silkscreen on board, 32 x 24 inches

Collection of the Vermont Historical Society, Gift of Alex Rothenberg

The King Story, 1967

Bread and Puppet Theater (1963-today), Founded by Peter Schumann (b. 1934)

Puppets (papier mache, paint, fabric, metal wire and wood)

Vintage archival film, c. late 1960s, filmed for Hollywood Television Theater

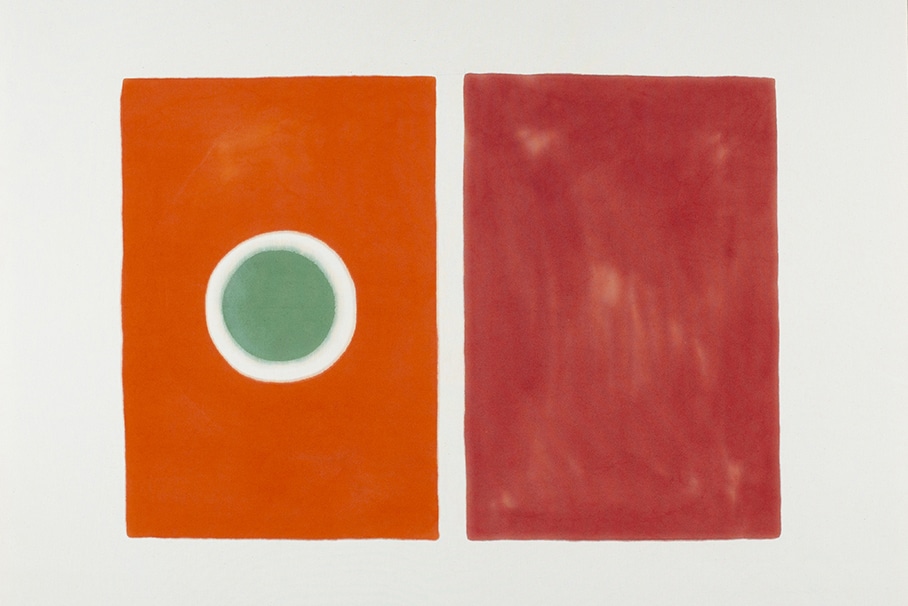

Paul Feeley (1910-1966)

Untitled (Green Eye), 1962

Oil-based enamel on canvas, 48 x 60 inches

Private Collection

Pat Adams (b. 1928)

Along and At, 1966

Oil and isobutyl methacrylate on canvas, 50 x 59 inches

Courtesy of the Artist

The 60s in Vermont – Defining the state as we know it today

This summer and into the fall, Bennington Museum presents two exhibitions that together tell the story of the changes that took place in the 1960s in the Green Mountain state. These changes helped to define the state’s artistic, social, political, and cultural landscape as we know it today. Fields of Change: 1960s Vermont is on view June 29 through November 3. Color Fields: 1960s Bennington Modernism is on view through December 30.

Fields of Change: 1960s Vermont examines the tumultuous decade that was filled with revolutionary change in America. Vermont did not go untouched. This was a period of dramatic, paradigmatic shifts in the social, political, and cultural identity of the Green Mountains: the construction of an interstate highway system brought flatlanders into Vermont in droves; the state’s politics shifted from a 100+ year Republican reign to a more balanced two party system, and an attendant openness to progressive ideologies took root; and the counterculture movement, including anti-war protests and an influx of back-to-the-landers, shifted the cultural landscape of the state forever. Color Fields: 1960s Bennington Modernism looks at a group of artists in and around Bennington College who led the country in their exploration of the possibilities of abstraction. Fueled by the changes taking place in the state, this group established Bennington as an epicenter for those exploring alternative art forms, a practice which lives on today.

CHANGES COME TO VERMONT

The Social, Political, and Cultural Climate

During the 1960s, many changes were afoot in the Green Mountain state. While some interactions were peaceful and led to open discussion, others had more serious consequences.

Romaine Tenney and a Highway Official Survey the Tenney Farm, Ascutney, Vermont, 1964 Donald Wiedenmayer (1917-2013) Inkjet print from scan of original negative, 10 x 12 ¾ inches Courtesy of the Vermont State Archives and Records Administration

Tensions ran high between long-time Vermonters who often held tightly to their traditional lifestyles, and the dramatic changes occurring around them. With tourism at the heart of the economy, construction of the interstate road system was designed to more easily bring in tourists and permanent or temporary residents to Vermont. This “improved” infrastructure, a defining characteristic of change in Vermont during the 60s, led to the attendant arrival of thousands of “flatlanders.” While this was met by some with less confrontation, other responses where quite severe. Romaine Tenney was a farmer from Ascutney. When the state attempted to purchase his multi-generation family farm to build the interstate, he refused to sell. The state took Tenney’s land by eminent domain. When the bulldozers arrived to raze his home and barns he released all the livestock, locked himself inside and lit his house on fire. He died in the blaze. Tenney died September 11, 1964. This dramatic episode illustrates the frequent tension between long-time Vermonters, who often held very tightly to their traditional lifestyles, and the dramatic changes occurring around them.

On the political front, in 1962 Phil Hoff was elected the first Democratic governor ever in the state of Vermont. For over 100 years, since 1856, the state was led by the conservative Republican Party. Hoff was an opponent of the Vietnam War and also fought to have reapportionment implemented. No longer would each town, regardless of its size, receive one vote. Districts would be apportioned by population shifting government to a more progressive and equitable stance. With Hoff at the helm, many young politicians found themselves working for change on state committees. Known as the “young turks,” these younger representatives moved the state to a more politically progressive government. This break from the more conservative hold led the way for moderation as we know it today with state government often shifting between Republican and Democratic parties.

Yet another point of contention surrounded the building of Bennington’s Mount Anthony Union High School, designed by award-winning architect Ben Thompson, and opened to students in the fall of 1967. The school was a physical manifestation of the dramatic turn many in Vermont were making towards more liberal ideas during the 1960s. Designed with progressive education in mind, such as open classroom concepts, the building won awards for its innovation. The school’s administration was leading a charge towards this progressive education. Liberal young teachers were hired, communal spaces were integrated, programs such as DUO (Do unto Others) allowed for independent projects by students curriculum geared toward a less traditional, independent study structure. These practices often stirred controversy in the community, but none as much as the design of a poster for a school play in 1969, Brecht on Brecht, George Tabori’s innovative sampler of the German playwright’s work. The poster featured a swastika overlaid on top of the American flag and a dripping, seemingly bloody font. Journalist Greg Guma, who reported on the local school controversies during the late 1960s, described the situation as “a struggle for power between two factions – working class traditionalists and middle-class modernists.”

Young Man Holding a Peace Candle at Vietnam Moratorium Rally, Bennington, 1969 Greg Guma (b. 1947) Inkjet print from scan of original negative, 13 ¾ x 9 inches Courtesy of the artist

The Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam was a massive nationwide protest on October 15, 1969. Again, Vermont was not excluded. The protest was particularly popular amongst a young rising activist generation who led what became known as the counter-culture movement. In Bennington, the Moratorium included a day-long door-to-door canvasing to provide local residents with information about the war and their desire to see it end. The then former governor Phil Hoff gave a speech at the Armory, and there was a community-wide rally around the Bennington Battle Monument that evening. Arnold Ricks, who was a college history professor at Bennington at the time, recalled protestors marching up Monument Avenue and around the monument. When they encountered some spectators who didn’t share their views, the entire group remained peaceful and broke out singing the classic Youngbloods ballad Get Together.

Peter Schumann studied and practiced sculpture and dance in his native Germany before moving to the United States in 1961, founding Bread and Puppet Theater in New York City in 1963. Bread and Puppet was an innovator in the field of grassroots, politically engaged activist performance. From hand and rod puppet shows in the streets to giant puppet parades, Schumann addressed local injustices as well as national politics and the Vietnam War. In 1970 Schumann and the theater company moved to Vermont permanently, first as artists-in-residence at Goddard College, then in 1974 establishing their current home on a farm in Glover, Vermont.

The King Story, 1967 Bread and Puppet Theater (1963-today), Founded by Peter Schumann (b. 1934) Puppets (papier mache, paint, fabric, metal wire and wood) Vintage archival film, c. late 1960s, filmed for Hollywood Television Theater

The King Story was one of Bread and Puppet’s early anti-war performances, first performed in 1963 and later at the 1967 Peace March on Washington. The plot of the play is simple, but carries a profound message. Against the advice of his priest and other advisors, the good king seeks the aid of a great warrior to protect his people from a dangerous dragon (or in this filmed version “a terrible giant blunderbore”). The warrior defeats the threat, but then turns on the king, killing him, his advisors, and all his good people.

Throughout the decade of the 1960s issues of civil rights were a regular issue in both the local and national news, and despite Vermont’s reputation as one of the least diverse states in the union, or perhaps because of it, Vermonters were quite active in this larger social movement. A little over a month after the now famous lunch counter sit-in at a Woolworths store in Greensboro, North Carolina, a group of Bennington College students staged a sit-in and picket protest at the Woolworth’s on Bennington’s Main Street. Though there was no regular policy of discrimination against serving blacks at the Bennington store, the students wanted to bring the plight of their southern brothers and sisters to light and protest Woolworth’s policies of discrimination in other parts of the country.

The Dawn of Color Field

On view through December 30, Color Fields: 1960s Bennington Modernism examines the artistic developments witnessed during the decade of change.

Inspired by the back-to-the-land movement, many young artists who made functional objects by hand with clay, glass, wood, and other natural materials, settled in Vermont in the 60s and early 70s. Cheap land, beautiful landscape, and a short commute to major metropolitan areas, were all reasons for the influx of this population. Beginning in 1969, and continuing for a few years through the early 1970s, the American Crafts Council held their annual Northeast Craft Fair at Mt. Anthony Union High School in Bennington. Vermont as a whole became the epicenter of the studio craft revival during the 1960s. But an equal or larger movement, led by the acclaimed art faculty at Bennington College, was also underway.

Paul Feeley (1910-1966). Untitled (Green Eye), 1962 (detail). Oil-based enamel on canvas, 48 x 60 inches. Private Collection

During the 1960s, Bennington College served as a rural epicenter for a group of avant–garde artists who were pushing the boundaries of abstraction in pared down, color based works that have come to be known collectively as Color Field. This exhibition looks at that critical moment when artists connected to and working in Bennington led the way in American art, while expanding our understanding of the variety of formal, material, and conceptual approaches to Color Field painting and related color-based sculpture. Seen in conjunction with Fields of Change: 1960s Vermont, the exhibition situates these artists and their work in relationship to the dramatic cultural and social changes that came to define Vermont during this period. Drawing on the emphasis of radical experimentation and Vermont’s storied landscape found in the counter culture and Back-to-the-Land movements, these artists also found Vermont to be a retreat from the more structured art scene of New York City, providing them with a setting for lively discussion and socializing. Bennington continues to serve as this enclave today. Work created by artists such as Pat Adams, Anthony Caro, Paul Feeley, Helen Frankenthaler, Ruth Ann Fredenthal, Patricia Johanson, Vincent Longo, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski during the 60s is on view.

About the Museum

Bennington Museum is located at 75 Main Street (Route 9), Bennington, in The Shires of Vermont. The Museum is open daily June through October (closed July 4.) It is wheelchair accessible. Regular admission is $10 for adults, $9 for seniors and students over 18. Admission is never charged for younger students, museum members, or to visit the museum shop. Visit the museum’s website www.benningtonmuseum.org or call 802-447-1571 for more information.

Bennington Museum is a member of ArtCountry, a consortium of notable art and performance destinations in the scenic northern Berkshires of Massachusetts and southern Green Mountains of Vermont, including The Clark Art Institute, Williams College Museum of Art , Williamstown Theatre Festival (20 minutes away); and MASS MoCA (25minutes away). Visit ArtCountry.org for more information on these five great cultural centers.