Anna Mary Robertson Moses was born September 7, 1860 in Greenwich, New York. Her father, Russell King Robertson, was a farmer and amateur painter. He encouraged her artistic interests. However, farming was hard work and for most of her life she considered painting to be a frivolous pursuit. At the age of 27, Anna Mary met and married Thomas Salmon Moses. After spending nearly twenty years in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, they returned to New York in 1905 and settled on a farm in Eagle Bridge, naming it “Mount Nebo.” It was here that Thomas died in 1927. As tending to the farm became physically challenging for a woman in her seventies, Anna Mary Moses began stitching and giving her embroidered pictures away. By the mid-1930s, as her arthritis gradually worsened, she turned to painting. Thus began Grandma Moses' career as an artist.

In 1938, Louis J. Caldor, a discerning New York City art collector, discovered Moses' paintings on display in the window of W.D. Thomas Pharmacy in Hoosick Falls, New York. He purchased all the paintings Moses had completed, and worked to find her representation in New York. That same year Alfred Barr, the founding Director of the Museum of Modern Art, declared that modern art was comprised of three distinct but equal “movements”: Cubism/Abstraction, Surrealism/Dada, and Self-Taught or “Popular” Art. Self-taught artists, often called folk artists or “primitive” painters, were hailed for their authenticity and intuitive picture-making skills.

In 1939 three of Grandma Moses paintings were included in a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. The following year she received her first solo exhibition, What a Farm Wife Painted, organized by Otto Kallir at Galerie St. Etienne in New York City. It opened in October 1940, a month after her 80th birthday. Kallir specialized in modern Austrian masters but was also interested in the work of self-taught painters. Kallir organized Moses exhibitions that traveled across the nation and internationally. Within a few years, Grandma Moses was a household name and her paintings were instantly recognizable to millions of Americans, printed on holiday cards, dinner plates, and curtain fabrics. In 1953 she appeared on the cover of Time magazine. In 1955 she was interviewed on live television by Edward R. Murrow. And in 1960 Life magazine did a cover story to celebrate her 100th birthday. Grandma Moses passed away on December 13, 1961, at the age of 101, having witnessed a broad swath of American history: she was born the year Lincoln was elected, and died while Kennedy was president.

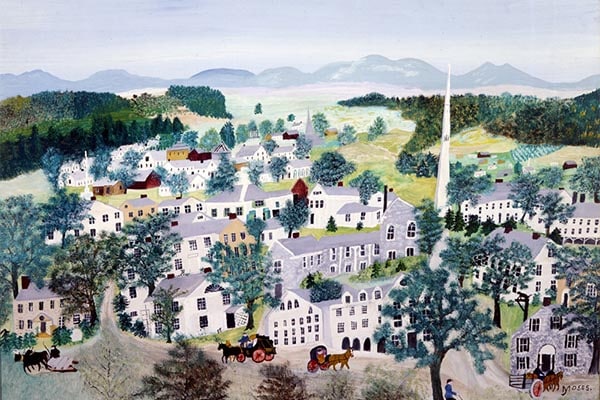

Grandma Moses’ paintings continue to captivate us today not only because they capture a sense of an idyllic bygone era in American life, but also for their abstract artistic values. She painted by intuition but was guided by a highly skilled and practiced sensibility. She had a remarkably sophisticated sense of color and texture. The elevated bird’s-eye view of her paintings allowed them to be about the general rather than the particular. Houses and barns take on elemental cubic forms. The rolling hills and fields of her native Washington County become a flattened patchwork quilt of color and pattern. Human figures have an iconic simplicity: children running, a farmer leaning on his hoe. Themes speak of the unchanging cycles of rural life: maple sugaring, the gathering storm, quilt making, a country wedding. This is why we return to her paintings again and again, for their intuitive artistic strength and their evocation of a timeless rural American past.